PASATIEMPO Sunday, January 8, 2017

JULIE SPEED: Solo Exhibition

Evoke Contemporary, 550 S. Guadalupe St., Santa Fe, New Mexico 87501 505-995-9902

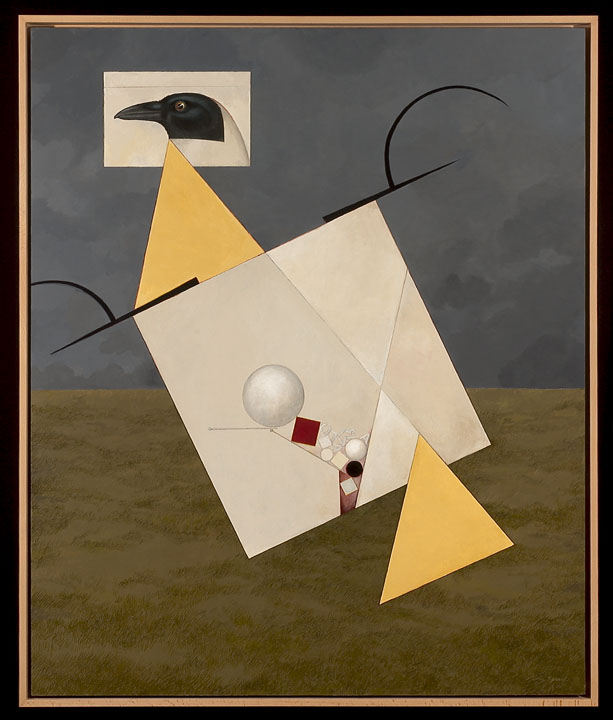

Hammerhead 2015 gouache & collage, 29.50 x 41.50 inches jpg 200 mb

Magic in the Mundane: Artist Julie Speed

Michael Abatemarco

In the gouache and collage paintings of multimedia artist Julie Speed, inanity and folly interrupt the mundane, heightening the drama of otherwise unremarkable moments. A tearoom becomes the setting for an act of torture, for instance, and a parlor scene becomes a surreal conflation of incongruities. The parlor scene, a painting called Hammerhead, depicts two women sitting on a sofa beneath historic Japanese art prints and an image of the Pietà. One woman is reading, while the other is grasping at a writhing hammerhead shark. You can wonder at the work’s possible meanings, but for Speed, meanings are subjective. They emerge from both the creation process and the mind of the beholder. “Because my work is mostly figurative, people assume that I start out with an idea or concept and then represent it,” she told Pasatiempo. “But I work the other way around. I start with the composition and, more than any other element, the composition drives the narrative.”

Speed’s first exhibition at Evoke Contemporary opens Friday, Jan. 6. It’s a traveling show organized by Austin’s Flatbed Press and Ruiz-Healy Art in San Antonio. Evoke is showing more than 50 works by Speed. An open-ended narrative sense makes her artwork enigmatic. Often, action is taking place, such as the small rescue boat on the sea in the painting Kunisada’s Ghosts, en route to a sinking house in the distance. But the relationship of this little drama to the central figures on the shore — a mix of costumed Japanese in the style of ukiyo-e woodblock prints made popular by Utagawa Kunisada in the 19th century, along with Speed’s own stylized renderings of people — clownish, slightly grotesque, and childlike — is unclear. We want Speed’s work to tell us stories, but here we have the prompts for crafting narratives of our own. You can look at her painting Milky Way, for instance — wherein military and political figures argue over a pile of skulls, with a pack of snarling wolves and a tantrum-throwing child getting in on the act — as an allegory of war. But the scene’s inclusion of the Milky Way, glimpsed through the windows, suggests something else — while leaders argue, the universe goes on, and will remain long after men and their petty squabbles die away. “Milky Way didn’t start out to be about war and its atrocities,” Speed said. “The geometric elements were in place early, so if it was going to be a completely abstract painting, the composition was settled. ... Then the news came of another horrific event in the Middle East. Sometimes the work changes in response to the news, sometimes to what I’m reading or thinking about, or sometimes for no reason that I can understand and point to, and while the painting may stop changing when it’s finished, my thoughts about it continue to change long after the work has left the studio. I love that other people think of things that would have never occurred to me.”

Speed works out of a studio in Marfa, Texas. Although she spent a brief period in the late 1960s studying at the Rhode Island School of Design, she’s mostly self-taught. She uses her mediums of gouache and collage to complement one another, blending paint and paper seamlessly so that her own draftsmanship and that of illustrators, whose images she culls for her compositions, are cohesive. Elements like the Japanese figures in her Christian-themed painting Good Friday might seem incongruous, but their inclusion reveals a deep-enough knowledge of art history, art movements, and their stylistic conventions to establish associations between them, conflating events and artistic styles separated by great periods of time. Her not-especially-flattering depictions of people recall the images of the unsophisticated masses in Dutch genre painting, like something by Pieter Bruegel the Elder (1525-1569). But they also recall the bardo figures of Tibetan Buddhist art, trapped as they are in cycles of ignorance, anger, suffering, and pain.

One can see the influence of Dutch vanitas still lifes in her work, too, which often contain memento moris, symbolic references to mortality that express a Christian view of earthly pursuits, antithetical to spiritual discipline. Undertoad, for example, shows a skull, a common memento mori in Western art traditions, attached to a leafless tree (the title comes from the toad nestled in its roots). But Speed’s take is less didactic than that of her forebears. Although she takes inspiration from Renaissance art, Dutch painting, antique medical and scientific journals, and the “Floating World” woodblock prints of Japan, among other sources, it isn’t to emulate them. Rather, she can use them materially, to cast them into re-imagined scenarios where these disparate artistic elements can continue speaking to us out of their original context. “The things that I’m drawn to, I’m not drawn to because they’re older,” she said. “I detest nostalgia. It’s their individual specific characteristics that I’m interested in. I understand that people think about art in terms of time, place, and subject matter, but I’ve never actually experienced it that way myself. For me, it’s all one.”

A dark sense of humor pervades Speed’s artwork, which straddles an edge between comedy and a discomfiting sense of irrationality. Her figures, often rendered as angry or bemused, seem as though they’re caught in situations of their own making, creators of their own Hell, with no cognizance of the fact that they’re in it. But that doesn’t mean they can’t elicit a laugh or two. Pope Descending is a case in point. In the painting, men argue over a game of cards with a cooked chicken, a vulva-like split down its center, resting between them. The Pope, meanwhile, can be seen through an open doorway as he is falling down a flight of stairs. “That painting was almost finished, and I’d painted the little figure in the background that has tripped on the dog and is falling down the stairs as a self-portrait. Then I remembered what happened last time I painted myself into a painting. About 15 years ago, in a painting called Tea, I painted myself as the figure in the window of a distant building with my hair on fire. That night we were invited to a fancy dinner party at the home of some people that I didn’t really know very well. During dinner, I leaned over the table for something and the candle caught my hair and it instantly ignited with a giant whoosh of flame. It was over in a flash, but the smell remained and pretty much ruined the party.” The memory prompted her to remove herself from Pope Descending and replace her image with the pope. “Then I started laughing because the pope falling down the stairs reminded me of Marcel Duchamp’s famous Nude Descending a Staircase, and so I decided to title the painting Pope Descending. The very next morning the first thing I saw on my computer was the announcement that Pope Benedict had just become the first pontiff since, I think, 1415 or so, to voluntarily ‘descend’ from the papal throne.”

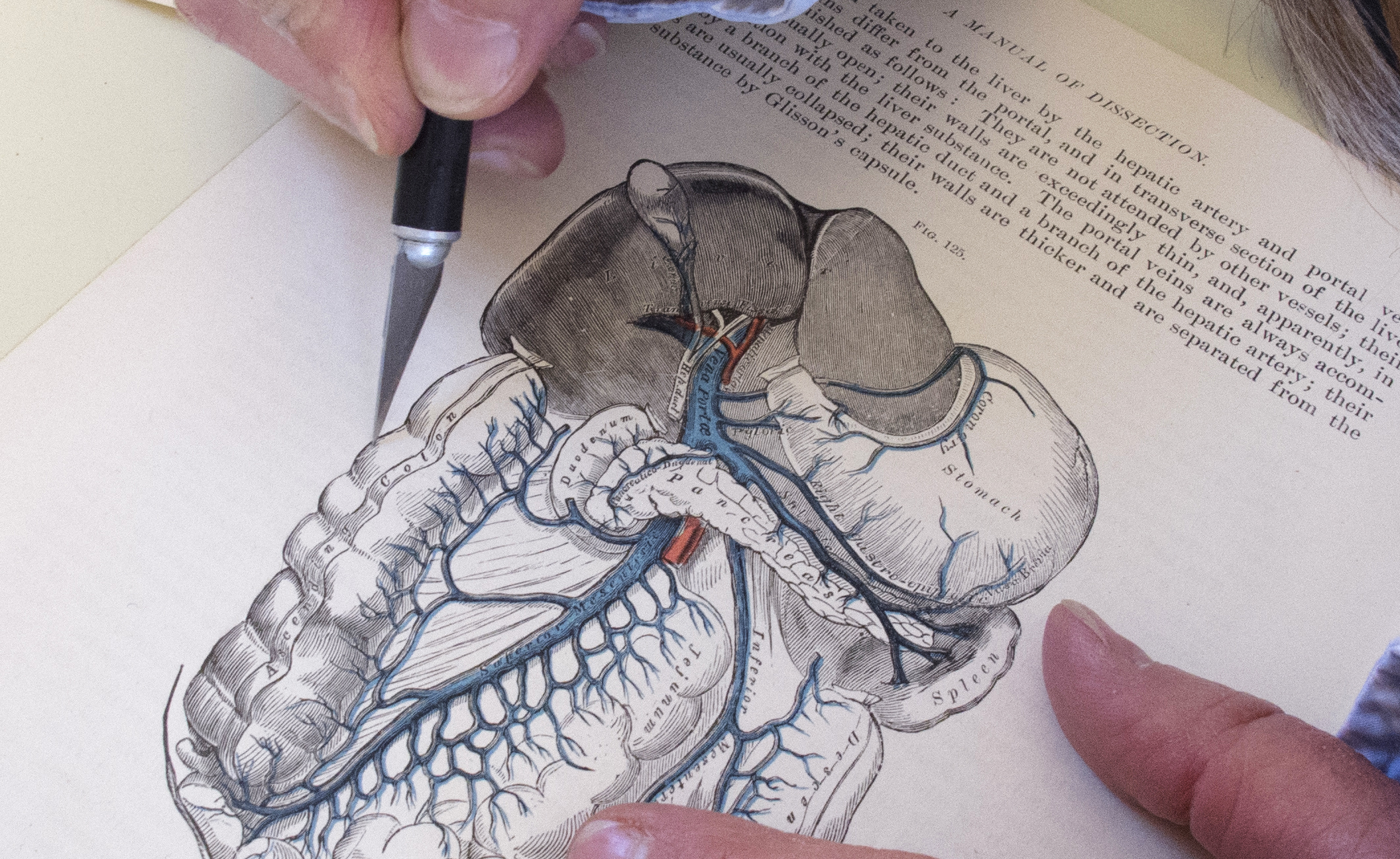

Not all of the work in the exhibit is narrative. Speed works in abstraction, too, but representational elements still come into play. Death and the Maiden, In Flagrante, and In Flagrante Again, for instance, contain molecular and amoeba-like figures derived from old texts. But even among protozoa, Death appears, shown here as a skull collaged onto the head of a spermatozoal form. “A lot of the collage elements that you notice in Death and the Maiden, In Flagrante, and In Flagrante Again are from Gray’s Anatomy,” she said. “Gray’s is particularly useful because it’s been in steady use as a textbook since the late 1800s, so there are a lot of wrecked copies out there floating around, and I find them regularly. Other collage elements are sourced from old biology textbooks, seashell engravings and silver pattern illustrations from a 19th-century art journal. I’ve been collecting wrecked books and pieces of books for almost my whole life.”

Speed stresses the importance of using books in disrepair for source material — she chooses to use found elements as they are, with little manipulation. “The rules to my game are that I’m not allowed to take apart any good books, use any internet-sourced material or my scanner and printer to blow anything up or down, so I buy what I can find at flea markets, eBay, and junk stores. Sometimes I find things while I’m out walking. The precipice in Precipice is a cement-mix bag I found blowing down the street. Fire, flood, and children are my friends, because they ruin the most books. Lately I’ve been finding and using a lot of 19th-century Japanese woodblock prints, so I’ve added worms to my thank-you list. Because the woodblock prints were done on paper made from the bark of mulberry trees, the worms can’t resist it.”

Death and the Maiden 2014 gouache, collage & ink, 40 x 60 inches

Julie Speed’s Engaging Puzzles for Inquisitive Eyes

The Rivard Report on 27 February, 2016 at 00:02

For Marfa-based artist Julie Speed, all the world’s a puzzle.

A painter, sculptor, collage artist, and printmaker who has been exhibiting for more than thirty years, Speed is currently presenting a recent body of her provocative and at times humorously enigmatic art in tandem exhibitions at Ruiz-Healy Art in San Antonio through Saturday, March 19, and at Flatbed Press and Gallery in Austin through Thursday, April 7.

A feast for inquisitive eyes, Speed’s exhibition at Ruiz-Healy Art features both representational and abstract imagery, much of which is delightfully overloaded with painstakingly crafted details. An avowed advocate of the philosophy that art is as much for the viewer as it is for the artist, Speed is of the school of artists who revel in open-ended content.

Years ago, believing that her own interpretation is only one of many possibilities for understanding what we see in her artwork, she coined the term “parareality” to refer to each alternative potential meaning, with the idea that no single explanation is any more valid than another.

Although Speed set out to be an academically trained artist, having studied briefly at the Rhode Island School of Design in the late ’60s, she is largely self-taught. Married to a musician, she spent a lot of time traveling in the ’70s, until she and her husband settled in the music-centric city of Austin in 1978. Once rooted, Speed began devoting more time to honing her skills as a painter.

During the ’80s, the period when she began exhibiting, Speed concentrated mainly on images of the human figure and, in some of her earliest paintings, her influences are fairly easy to identify. In “Ring of Fire” (1985), a well-dressed couple standing in the rain on a beach in a circle of fire and holding an umbrella is an obvious homage to a visual artist and a musician, with the imagery recalling that of the Surrealist painter Rene Magritte, and the title inspired by the popular Johnny Cash hit.

While Magritte-like stylistic elements are also evident in the subsequent painting “The Grand Dragon Crossing the River Styx on His Way to Hell” (1989), as in the irrational river composed of watermelons, this is one of the few works in Speed’s oeuvre that was actually conceived in response to a specific issue — the horrific practices of the Ku Klux Klan. As has become her custom, Speed freely blends references from diverse sources and here joins a biblical image, a crucifixion, to a mythological place, the River Styx, to create a new fictional reality in which the Klansman is on the stake, with a Black rabbi and nun as overseers and the watermelons as symbols of racial stereotyping.

The Grand Dragon Crossing the River Styx on His Way to Hell, 1989 oil on panel

“She Asked Why,” 1988, ink and watercolor.

A number of Speed’s early paintings take on the guise of simple portraits. None, however, are of people who actually exist and the imagery is more complex that it might at first appear. In “Queen of My Room III” (1998) and “Please Help Me, My Brain is Burning” (1994), invented female characters appear isolated against barren backgrounds as they stare blankly towards the viewer.

As in “Ring of Fire” and “The Grand Dragon Crossing…,” both paintings use subtle references to fire to invite narrative interpretations suggesting, for example, that the women’s expressionless faces are masking something deeper. In “Queen of My Room III,” the woman holds a lit match, and her crown is actually made up of matchsticks. So reflective viewers may begin asking themselves, “Is she a housewife trapped in a prison of domesticity, or is she a self-anointed practitioner of arson?” Both explanations, as well as others, are legitimate.

And whether it is a crown, a halo, a hat, or simply her hair on fire, the flames behind the woman’s head in “Please Help Me, My Brain is Burning” hint at inner anguish and discontent, which is reiterated in the title phrase being inscribed in Latin and moving laterally through the subject’s ears.

As potent as potential narratives that may be extracted from Speed’s paintings seem to be, it would be to misconstrue the artist’s intentions to assert that, other than in a rare example such as “The Grand Dragon…,” iconographic content is a motivator of the work. First and foremost, Speed is a formalist, who develops a composition using a trial and error process that is based on aesthetic considerations. In “Queen of My Room III,” in fact, the inclusion of the woman’s hand with the match evolved from a desire for compositional balance. Only after it is in place does it begin to stimulate potential narrative or metaphoric content.

“Please Help Me, My Brain is Burning,” 1994, oil on board

Speed’s delightful inventiveness when it comes to composition can be seen reaching a point of mastery in her ink and watercolor drawings of the late ’80s, where she subverted normal expectations by adding bits of color to isolated details within black-and-white compositions. While such compositional embellishments have become common features in today’s digitally manipulated imagery, Speed’s actions predate the digital era, and she works only with her hands, computers are verboten.

Patterns abound in these compositions as well, and the space is deliberately distorted. So nothing appears logical, as we have traveled through the rabbit hole and thus the questioning can begin. With the title phrase “She Asked Why,” in fact, Speed gives us a subtle directive to start imagining what might be going on, and she reinforces her instructions with the finely detailed book of questions on the woman’s lap, and the puzzled expression on her face as she ponders a sliced-open lizard.

In the ’90s, Speed expanded her repertoire of mediums to include three-dimensional objects. For one series, she filled shadow boxes with painted cutouts and actual thorns, which serve as architectural backdrops. “Thornboxes” (1992), for example, is a compositional hybrid of a Renaissance altar and a Joseph Cornell boxed assemblage.

Concealed behind glass and protected by a padlock, a secret narrative is taking place as two men stare silently at one another, their ears covered by the hands of others in a gesture that suggests the familiar cliché “Hear No Evil.” In the more minimal found object sculpture “The Reluctant Witness” (1999), Speed pays homage to the Surrealist objects of artists such as Man Ray, who created a number of metronomes with solitary eyeballs in the 1920s.

The Reluctant Witness 1999

Although the temperament of Speed’s art is consistently offbeat and quirky, she is one of those artists who has no singular style. As a keen observer and admirer of all kinds of art, she has listed among her many influences Early Byzantine art, Northern and Southern Rennaissance painting, Russian art and icons, Mughal and Persian miniatures, Australian Aboriginal art, 19th century Japanese woodcut prints, Manet and Degas, and numerous twentieth century artists including Pablo Picasso, Kasimir Malevich, Otto Dix, Balthus, Francis Bacon, Lucien Freud, and the self-taught artist Bill Traylor.

So, it is not surprising that she can move back and forth with great ease between representational and abstract imagery, as she did in 2003 with the painting “Still Life with Suicide Bomber #3″ and the painted collage “The Murder of Kasimir Malevich #8.”

Still Life with Suicide Bomber # 3 2003 oil on panel 15 x 15 inches

The Murder of Kasimir Malevich # 8 (Cropduster) 2003 acrylic & collage on panel, 36 x 30 inches

“The Murder of Kasimir Malevich #8,” 2003 (Cropduster) acrylic and collage on panel.

Although still working improvisationally during the first few years of the Millennium, Speed could not avoid creating these darkly sinister works in response to 9/11 and its aftermath. The abstract painter Malevich was not murdered, of course, but using his geometric style as a compositional starting point, Speed created a haunting image of a torn-open envelope with tablets emerging from it , bringing to mind the nationwide scare over the terrorist mailings of Anthrax.

Since moving to Marfa in 2006, Speed has devoted a lot of her efforts to making painted collages from her extensive collection of book illustrations. Since “Speed’s Law” dictates that she must never destroy a perfectly good book, damaged editions and loose leafs purchased separately provide resource materials for her creative endeavors.

As always, a work begins as Speed finds an interesting image to cut out and move about freely on paper, which is often another illustration that serves as the initial starting point and backdrop for an invented scenario. In “Suzanna, Annoyed” (2012), which is on view at Ruiz-Healy, the nude figure of the mythological Danae was cut from an illustration of her as depicted by Titian and his workshop and superimposed over another classical scene, striking a fine balance between the dominant foreground and the recessive background.

To fictionalize the figure further, Speed painted over her face, giving her a disgruntled expression, and brought her flesh to life by coloring it with a faint rosy tint. In this tiny scale work, she also brilliantly activated the background with droplets of red and yellow paint to create miniature explosions that echo the woman’s obvious discontent. Although Speed titled the work after the biblical Suzannah, who was accused of debauchery by lying elders, the scene could just as easily be interpreted as a contemporary woman who is fed up with the abuses faced by women in a world dominated by male power structures.

Indeed, Speed’s imaginary narratives often seem so incredibly well suited to the current issues of the day. In the recent painting “Milky Way” (2014), Speed has put a beautifully contemporary spin on the kind of satire that was practiced in the 16th century by yet another “elder,” Pieter Brueghel the Elder. Like Brueghel’s “Blind Leading the Blind” (1568), in which foolish people follow their leader one-by-one into a ditch, Speed’s “Milky Way” similarly calls attention to the futility of human folly.

Reminiscent of today’s politicians, three male dignitaries from different cultures and time periods as indicated by their garb may be plotting the world’s future, as an angry woman (a Trump supporter perhaps?) cheers them on. While hungry dogs in the right foreground suggest that the power figures will ultimately swallow one another alive, skulls on the table and windows opening on to star-filled nighttime galaxies are reality-check reminders that all human activity is transient, that political tides come and go, and that life as we know it is just a momentary spec on the boundless universe of space and time.

CATALOG ESSAY FROM:

JULIE SPEED - PAPER CUT: SELECTED WORKS ON PAPER

THE GRACE MUSEUM -SEPTEMBER 12, 2014 TO FEBRUARY 14, 2015, ABILENE, TEXAS

My studio used to be the jail for Fort D.A. Russell, a former calvary base on the edge of the town of Marfa, Texas about 60 miles north of the Mexican border in the Chihauhuan desert. It’s a big building so I’m lucky to have a separate space just for collage.

I’ve been collecting wrecked books, moldy magazines and worm-eaten and water damaged engravings from flea markets and yard sales for most of my life. When I walk to town to pick up the mail I almost always come home with a few bits of metal or wood that I’ve found along the road or railroad tracks. Sometimes people send me things. My cupboards are full.

Because of the infinite possibilities involved with working in collage and because too many choices make you crazy, I limit my materials by a couple of rules. First one is: no tearing up good books…. so fire, flood and children are my friends. Second rule is no using the computer. If I need to alter something I alter it with a tiny brush and paint or a knife. Some sections I paint entirely with gouache so the finished work often ends up much closer to a painting than a collage. Sometimes vice versa. Sometimes the collage pieces I add are dimensional so the work turns into a box.

To begin, I use an exacto knife to cut out the pieces, sort them into rough categories, then pick up a piece that I particularly like and paint the edges of the paper with a warm gray gouache to camouflage the cut. Then I’ll pick up a dozen or so other pieces that look like they belong with the first piece and paint their edges also.

Next, using a reversible pressure sensitive putty, I start positioning the first pieces onto an Arches paper ground. The size of the pieces that I start with dictates the size of the ground. Sometimes it takes a couple of days to get the first 3, 5, or 7 pieces right. Each time you add an element or shift one of the pieces even slightly then the distance/weight relationships between all the other pieces also change, so balance is a constantly moving target.

When the anchor pieces are right, I glue them down with acrylic matte gel, using an etching brayer and/or rolling pin with repeated pressure to squeeze out the excess gel. Then I weigh them down overnight with heavy pieces of glass. If there’s a lot of mold on the paper I’ll later add a top layer of gel medium to stabilize it.

The next day I start to paint. I’ll paint for a while, then add another collage piece and on and on back and forth. If I need to cut a larger or very complicated piece of paper, or if I need to glue several pieces to each other before gluing them to the ground, I’ll use a pencil and tracing paper to demarcate where the knife goes and where the glue goes. Most of the collage pieces that I originally altered with a knife I’ll alter many times again with a brush and paint.

With each added element, whether paint or collage, the possibilities multiply. As the days go on, the visual equation becomes exponentially more complicated. The more complicated it is, the more fun it is.

This piece, Death and the Maiden, is one of a reoccurring series that I’ve been working on, on and off since 2007. I call them “floaters”.

They began with a winter trip down the South Texas coast where on a deserted beach we found what seemed to be some kind of grim jellyfish Jonestown involving thousands of Portuguese man o’ war. The sand was littered with their bodies…amazing blue and purple and green and pink glistening jellies…some of them still living. So I started to think about what their tentacles would look like moving in the underwater currents, then that expanded to thinking about everything that floats and how it moves and the spaces in-between.

From tentacles it was a short hop to dendrites and neurons and from there to other body parts, both visible and microscopic. What’s swirling inside us looks remarkably like what’s swirling in the deepest oceans and the night sky also. Body parts, shells, plant parts, nebulae, splashes and explosions are all similar in structure and seem to lend themselves to being combined, painted and alteredin as many combinationsas I can possibly invent with a knife and paint. It’s an endless puzzle ……which is the whole point really because the satisfaction for me is in the work.

Julie Speed, July 2014

Turns out Men O’ War aren’tjellyfish at all, or even a single animal. They’re a colony of zooids, individualorganisms which cannot exist on their own.

The Moral Painter

by Elizabeth Ferrer

(Courtesy of the University of Texas Press)

The Art of Julie Speed

The contemporary art world has long maintained an awkward relationship with realism, especially with work that does not intend to offer a postmodern critique of, say, the power structures implicit in older Western art styles or the objectification of the human figure. What was for a very long time highly esteemed in a painting or drawing—the sense of verisimilitude that could conjure for a viewer what something was like, through the masterful evocation of three-dimensional form, textures, or the play of light and shadows—is now largely viewed as obsolescent, even unnecessary. This approach to valuing a work of art waned in the mid-nineteenth century in large part as a result of the emergence of photography, which acted to supplant painting as the visual medium best able to provide an index of reality. Later in the nineteenth century, a succession of painterly styles, beginning with impressionism and continuing through such movements as pointillism, postimpressionism, and fauvism, continually diminished the appreciation for technical mastery that was central to painting for several centuries.

But alongside the rise of modernism, there were always artists who found new motivations for returning to the realist mode. Some were driven by the desire to directly convey social or political messages, such as the artists associated with the Ash Can School in the United States early in the twentieth century, or the social realists in the Soviet Union beginning in the 1930s. By mid-century, even as the avant-garde in the United States and Europe increasingly embraced abstraction and then conceptual modes, in Latin America much attention continued to be focused on artists who demonstrated exceptional technical virtuosity. This is seen, for example, in the work of such figures as the Chilean realist Claudio Bravo and the Cuban landscape painter Tomás Sánchez. By the 1960s, realism also enjoyed a revival in the United States, thanks to the prominence of figurative artists like Philip Pearlstein, Alice Neel, and Chuck Close, as well as to the vogue for photorealism exemplified by the paintings of Robert Bechtle, Audrey Flack, and Richard Estes. Nevertheless, these artists represented a minority, especially amid the growing pluralism of visual styles in this and subsequent decades. Painting may have never died, but fewer and fewer younger painters (and their teachers) in recent decades have placed a priority on acquiring the fundamental skills that artists once persevered to attain.

But Julie Speed is different. In stark contrast to her contemporaries, over the last two de- cades she has worked assiduously to develop the artistic means by which to realistically render the human form. She can expertly depict the tonalities and translucency of skin, as well as the fleshiness and furrows of the imperfect body. When Speed depicts the human eye, she is not only adept at showing the way that light reflects upon its surface, but she has also developed an impressive repertoire for representing it in an array of heightened emotional states.

Unlike artists of earlier generations, Speed paints this way not to convey outward appearances and physical realities, but rather as a means of posing open-ended questions for herself and the viewer; realism allows the spectator to get into her head. To gaze upon a Julie Speed canvas is to enter an unusually rich interior world, one formed by stories and myths, history, and complex associations among all the things that she thinks about and experiences. Her composi- tions do refer to real things—whether to events in her own life or to those taking place in some distant part of the world—but filtered through a mind that is unusually keen and imaginative, and that is preoccupied by a desire to make sense of the absurdities that permeate the contemporary condition.

Many commentators have characterized Speed’s paintings as a kind of latter-day surrealism, a conjuring of dreams and of the disjunctive realms brought together in the subconscious. The founder of surrealism, André Breton, noted that a central aim of the movement was “to resolve the previously contradictory conditions of dream and reality into an absolute reality, a super- reality.”1 Based on this ideal, figures like René Magritte and Salvador Dalí were drawn to realistic modes of depiction, even if they were using them to imagine clouds inside rooms (Magritte) or melting clocks (Dalí). Speed, however, has never claimed inspiration from dreams. In the past, she emphatically noted that the images in her paintings came to her fully formed, whether while sitting at home in the bathtub or driving through the vast emptiness of West Texas, the place she now calls home. In recent years, she has spoken of a more elaborate process of artistic creation, one tied to formal and technical concerns but also to happenstance and whimsy.

Formany years Julie Speed has depicted enigmatic characters, eccentric men and women of uncertain age and time period. The men are often figures of authority, especially religious clerics and military generals. In contrast, the women are less clearly defined; they enact private dramas and maintain a mute presence in the face of impending calamity and inner demons. Speed’s women typically inhabit claustrophobic interiors, compact spaces that display only the scantest evidence of a domestic life (most often, a table displaying food or a card game). When her figures are alone they tend to gaze outward, their faces brimming with emotion. Seen in pairs, as in the paintings Evil Twin and Frogpond, they engage with each other warily, typically lost in their own individual worlds. Increasingly, she depicts large groups (often of men, sometimes completely or near naked), whose actions inevitably descend into crude, if farcical, violence.

Julie Speed portrays her characters using an old master technique that she has practiced for many years, one that endows them with a stark sense of realism. But even as they so plaintively manifest the anxiety that is a hallmark of contemporary existence, they clearly are not of our world; rather, they seem to inhabit some out-of-kilter, parallel world. These invented figures— they are never based on real people—function like doppelgängers that have been conjured to bear the weight of our collective trauma. Speed depicts them as if they are in a permanent state of emotional overload, unable either to escape their plight or to make sense of it.

During the slow process of painting Speed begins to understand where these figures come from. For example, The Cup, a scene of three men arrayed around another male figure whose chest has been cut open and is dripping blood into a cup, came as a result of Speed playing around with abstract forms on the linen canvas. The artist saw the arrangement of circles she was making as a grouping of men’s heads. While continuing to paint, she also discovered that the overall triangular arrangement of the figures created a relationship among the men; she then elaborated the details in the composition until she arrived at its final form. Only later did she recognize the presence of Christian symbols and the painting’s resemblance to traditional compositions of Christ’s descent from the cross. But at the time of painting, Speed had indeed been thinking about religion, about the role it plays in international power struggles and why some people adhere so unquestioningly to archaic or absolutist beliefs. Ultimately, The Cup acts as a satirical reworking of the Deposition, a theme that signifies Jesus Christ’s mystical nature and his act of martyrdom to save humankind. The work provides an alternative reading of an old theme, connecting humankind’s voracious appetite for violence with blind reliance on belief sys- tems. But, for Speed, such an interpretation can only be an end product; attempting to initiate a painting with such an interpretation in mind, she states, is a clear formula for failure. Just as significant is the process of painting, the way color and form animate the canvas, and the varied responses that such a work elicits in viewers.

The Cup 2006-07 oil on linen

Speed has long produced an impressive range of works in other formats—collages, prints, sculptures, assemblages, and works that mix varied media. These works are lesser known but, for the artist, they share equal importance with her paintings and works on paper. She has developed a mode of working with printmaking, collage, and other formats that offers her a completely different creative approach. For all the exacting care that Speed puts into the creation of collages, these works do not take nearly as long to complete as a painting. As a result, she can more freely experiment with new materials and techniques, as well as produce suites of works that play out variations of a single visual theme.

Much of this work is made possible by the fact that Speed is an inveterate collector of obscure, out-of-print books; old prints found in thrift stores; and pieces of metal and junk that she picks up during long walks along the train tracks near her studio. She is drawn to such arcane objects because they provoke in her an immediate, even if unexplainable, emotional or aesthetic response. The result of this collecting is often collages or, occasionally, small three-dimensional works created to give visual clarity to thoughts and to visual stimuli. One example is Black Squares, a series of fifteen works united by the inclusion, in each, of an identical dark aquatint square printed on a sheet of paper. The collage elements added to each of the surfaces in this series were bits of Speed’s “railroad junk” and found images that she has saved over the course of years, even decades. Working in this way, employing a fixed visual format combined with an array of materials, she is able to play out an idea and work with things, producing distilled poetic statements through incongruous pairings.

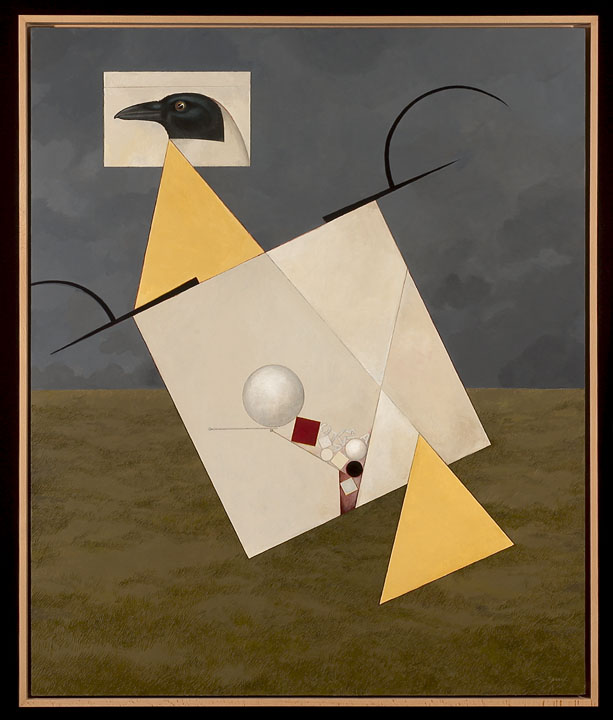

Speed also occasionally pursues the creation of a discrete series that embodies a small obsession, or that responds to a desire to experiment with a specific theme or artistic technique. One such series is The Murder of Kasimir Malevich, consisting of mixed-media works on paper that reflect her recent preoccupation with the disparate realms of birds, the modern Russian artist Kasimir Malevich, and world politics.

In 2004 Speed purchased a smoke-damaged, mid-nineteenth-century volume, Reports of Explorations and Surveys, one of several monumental exploration surveys commissioned by the United States government during an era of fervent expansion. The scientific illustrations of birds she discovered inside the book stopped the artist in her tracks; these are precisely the kinds of images that speak to her so viscerally that they can move her to pursue an entirely new body of work. During this period, in 2003 and 2004, she was also studying the suprematist canvases of Kasimir Malevich and thinking about the way this pioneering modernist infused meaning and emotion into a nonrepresentational art of pure color and geometry. Speed had experimented with abstraction only tangentially up until then, primarily through the sculptural objects she some- times produced from found materials. Even if her artistic mode would seem to bear little relation to Malevich’s highly reductive proto-minimalism, a close study of his paintings provided her with an appreciation for geometric form that had a considerable impact on how she would commence working on a blank canvas and develop a composition. And in his writings, Malevich equated his abstract forms with pure feeling, suggesting for Speed the possibilities of merging a more delib- erate approach to art making with her idiosyncratic, emotionally charged subject matter.

The artist’s discovery of the nineteenth-century bird illustrations provided her with the inspi- ration to produce a body of work, The Murder of Kasimir Malevich, unlike anything in her oeuvre. The series functions as an homage to an iconic modern master, one that wrestles with the art- ist’s faith in the abstract and, concomitantly, his rejection of physical representation. Speed’s images in the series act as experimental hybrids, combining representational forms (fragments of the bird illustrations) with abstraction, collage, and painting. Yet they are pared-down images, simple and direct. The compositions treat the birds as geometry, and geometric forms inspired by Malevich’s paintings as dynamic, organic matter.

As for the series title, Kasimir Malevich was not murdered, of course—he died in 1935 after a long illness. But John Jenkins, the legendary Texas antiquarian from whose library Speed ac- quired the volume with the bird pictures, might himself have been murdered. Plagued by allega- tions of fraud and forgery connected to his high-profile book dealings, his body was found on a public boat ramp in 1989, and it is unknown whether he was killed or committed suicide. And mysterious forms of death were also on Speed’s mind at the time she was making the collages because of the 2001 anthrax attacks, followed by growing anxiety over the possibility of mass biological warfare. One work in the series directly addresses this state of dread: a bird’s body contains a jumbled arrangement of letters that spell out “variola,” the Latin name for the small- pox virus. Tracing the accumulation of influences that contribute to such a series, it is possible to understand Speed’s collages as a diaristic art form that can weave together a remarkable set of disparate yet connectable influences: in the case of these works, Malevich and the early his- tory of abstraction, Texas and U.S. history, and an alarming incident of terrorism.

The Murder of Kasimir Malevich # 8 (Cropduster) 2003 acrylic & collage on panel, 36 x 30 inches

A lucky find was also responsible for the images comprising the 2005 Bible Studies series, a large group of etchings and mixed-media works combining drawing, collage, and printmaking techniques. In the mid-1990s Speed visited a used bookstore in Galveston where she purchased a box of water-damaged illustrated books; it would provide her with source material for years of collage making. Among the items was a Swedish Bible dating to the 1870s, with illustrations by the French engraver Gustav Doré. Speed began to cut out and combine various Bible scenes for a series of images, among them the repeated portrait of a cleric who gazes pensively outward. His clothing is covered with numerous fragments of engraved Old Testament scenes, through which Speed wittily transformed the figure into a living embodiment of fire-and-brimstone religi- osity. By wearing a robe filled with scenes of burnings of heretical texts, the cleric also acts as a symbol of censure, a mute castigator of free expression. In Ad Referendum, the dense collages of Bible scenes provide narrative and context, while the portrait of the cleric acts as a constant, the visual element that Speed says she needs when creating works in series “in order to make the game interesting.” The background becomes the variable, an expressive zone that offers shifting readings of the same central image. In successive images, the cleric is surrounded by jellyfish, fireworks, and bubbles; he also has a bird perched on his head or shoulder. A few images have additional collage elements, strips of handwritten or typed text, and, in one, cigar bands. Ulti- mately, the cleric is treated as a less-than-solemn figure, a passive witness to Speed’s insertions of overblown drama, bits of random information, and a sardonic phallic reference.

History is obviously rich source material for Julie Speed, but even more important is the present day. She has always used her work to tackle the big, universal is- sues that never go away—the struggle between good and evil, the quest for wisdom, the need to make sense of our lives. Rarely, however, does she render details that could tie her protagonists to the present day or to any specific moment in history. Speed casts her figures as oddball every- men or women who could ostensibly inhabit any time or place. But, to my eye, they make sly allusions to the conditions and social conventions of an exhausted European culture. In much of her work from the 1990s Speed seemed to relish evoking the style of the courtly portrait painting that began in the Renaissance, the northern European still-life tradition, and the interior worlds (physical and mental) of Vermeer’s women. Her paintings of cardinals and bishops are rooted in the portrayals of powerful religious men by artists like Raphael and Titian. But as Speed’s images around this theme have became more irreverent—she has depicted cardinals partially nude, gambling, and posing with monkeys—it has become difficult to look at them without thinking about the sexual scandals that mired the Roman Catholic Church in the 1990s and early 2000s. Certainly, Speed was thinking about this controversy as she depicted clerics dressed in elaborate vestments, but, to her mind, these canvases were as much about her desire to work with brilliant cadmium red paint as they were about the increasingly compromised state of Ca- tholicism in the United States.

For Speed, this less direct engagement with the here and now changed on September 11, 2001. In the painting Damage, completed in early 2002, she portrayed a figure with a bandaged head who turns to meet the spectator’s gaze. The scene visible through the window behind him is of dozens of minute bodies falling in the sky, all aflame. Perhaps the most topical work of art Speed has ever created, Damage is an unambiguous evocation of the terrorist attack on the World Trade Center. (It is illustrated in the 2004 volume Julie Speed: Paintings, Constructions, and Works on Paper.) Speed has often painted scenes of calamity and disaster (multitudes of drowning swimmers in The Bather and Bandwagon, careening tanks visible outside the window in Witness), but this painting acknowledges that no disaster imagined by the artist could surpass the real horror of multiple humans leaping to their sure death.

Since that time, the artist has only once come so near to mirroring the world close at hand, with four paintings from 2003 that share the title Still Life with Suicide Bomber. Each depicts a table displaying fruits along with severed body parts. The canvases horrify us in much the same way that extremely violent movies do, conjuring evil with an almost comic implausibility. These are unnerving images, less for their goriness than for the fact that they clearly reference the real- ity of our times. Speed notes that these compositions have more to do with “the moment just before—or after—something really bad happens” than with the actual phenomenon of suicide bombers in Iraq or elsewhere. Nevertheless, the climate of anxiety inaugurated on September 11 has had a lasting resonance in her work.

Ultimately, Julie Speed’s work argues for a kind of morality, one that has everything—and nothing—to do with politics, religion, nationality, and ethnicity. She deals frequently with the related themes of organized religion and power structures, examined from the uncommon van- tage point of one whose father was a scientist and who was, as she says, “raised with fairy tales before Jesus.” She has long viewed faith systems (especially the most dogmatic ones, like evan- gelical Christianity) as being akin to a belief in magic, and she expresses fear regarding those in power who believe in and base decisions on magic instead of science and knowledge. “I like to garden, bird watch, cook, and move rocks around in my garden,” she says. “There’s the possi- bility we could all live like that. But instead, we’re arguing about whose invisible friend is cooler than whose invisible friend.”2

Speed’s morality, then, comes down to the individual. With her paintings, whether of figures bearing the scars of some unknowable trauma or of groups engaged in absurd acts of violence, Speed emphatically suggests that the stakes for the future of humanity have become too high. She tackles the big issues by revealing the human condition in its most raw states, whether at ex- tremes of lucidity, bafflement, or arrogance. It is in these most intense moments of intellectual and psychological engagement that life has the greatest potential for good or evil. And Speed, who thinks with incredible breadth and circularity, would take us back to Kasimir Malevich and to his mission of articulating a form of art based on pure feeling. Malevich concluded that an abstract language best suited such a quest. Speed, even if known for her figurative painting, doesn’t necessarily come down on one side or the other; some of her mixed-media works and sculptures are highly abstract. But in her painting, pure emotion is just that, displayed starkly on the faces of imperfect characters. This is why the act of painting, and the ability to paint well, remains such a high priority in her artistic practice—it allows her to invent figures that can most vividly reflect life stripped to its bare essentials. Neither real nor unreal, they just exist timelessly, before history and after history, defiantly beating the odds.

ELIZABETH FERRER, NEW YORK October 2007

JULIE SPEED, INOCOCLAST

BY BARBARA ROSE

She has a determined look on her face, this dark, muscular nude woman with the overly prominent nose wearing what looks like a red bathing cap decorated with tiny starfish on her head. Slung over her shoulder is a huge gold colored fish that might once have float- ed in the pond of a Mandarin prince. Or could it sim- ply be a monstrous version of the little goldfish in glass bowls that were sold in five and dime stores, when Woolworth’s was still in business. You have never seen this woman before, yet she is strangely familiar. You conjecture she must be the artist's doppelganger because she appears in various situations and positions in so many of her works. But a photograph of the artist reveals she is small, silver haired with delicate fea- tures, so this hypothesis cannot be correct.

We will, of course, never know who Julie Speed's Swimmer is since she never existed except as a figment of her wildly creative imagination. Fish appear within many of Speed's mysterious tableaux, including the recent Fishmonger (p. 48), whose bloody apron tes- tifies to sacrifice, and whose open mouth expresses horror at what he has done. Speed is aware that fish are loaded with Christian symbolism, but her intention is not to evoke scripture; instead she seeks to expose a multiplicity of often opposing meanings as in The Sinner.

Speed fearlessly mixes memories of the Old Master paintings she loves with images from fairy tales, poetry, trash novels, thrift shops, Baroque prints, newspaper photographs, and Persian and Indian miniatures, blend- ing them together with everyday experiences and fantasies. The results of such wide and deep excavations inevitably address the Collective Unconscious so dear to Carl Jung and James Joyce.

Chinese cooks often keep a "master soup" on the stove to which they add daily leftovers until the stew becomes so rich that the original ingredients dissolve into an unfamiliar but delicious stew. Speed arrives at her complex and ambiguous images by adding layers of associations and memories, the residue of her experi- ence which is gradually enriched by time merging into a synthetic image whose sources are no longer distin- guishable. She has described this continuous process of image enrichment as follows: "The hambone that got thrown in circa 1958 is indistinguishable from the shallots I added in 1994. The pot’s been boiling for fifty years so it’s really hard to recognize the individual ingredients anymore. "

Born in Chicago, the restless artist spent most of her early years in New England. Her high school art teacher, Spanish painter Narciso Maisterra taught her to love both Francisco de Goya and Francis Bacon, who remain among her heroes. By now, her personal pan- theon includes Giovanni Bellini, Andrea Mantegna, Piero della Francesca, Sandro Botticelli, Rogier van der Weyden, Hieronymous Bosch and the popular illustra- tors Edward Gorey and Maurice Sendak, as well as anonymous Australian Aboriginal painters, and most recently, Kasimir Malevich.

Speed has painted all her life. Her marriage to a musician initially led to a peripatetic existence that was not conducive to executing work that required ample space and uninterrupted time. Since settling in Austin, Texas in 1978, she has been able to concentrate on perfecting her unique painting technique. She does not calculate her images; they appear to her as in a vision. When she visualizes a picture, she immediately does small sketches, which she stashes in drawers to preserve for future use.

When she is ready to start a new painting, she does rough preliminary sketches of the essential shapes in order to figure out the basic geometry of the compo- sition. We forget how deliberately composed the images are because the finished work is so strong and complete. Once she determines the size and shape of the image, she decides on its relation to the field, which fixes the dimensions of the support she will prepare. This is, of course, opposed to the way figurative painters normally work, accounting for the contempo- rary feeling of Speed’s art.

After executing a drawing, which has all the fine detail and delicate line of a Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres drawing, Speed digitally photographs it, so as not lose the image once she begins painting. At other times, like Bosch, she will paint alla prima, directly on the surface without any underlying sketch. She enjoys the smell of the paint and the physical pleasure of working. She claims that she has used and will use just about anything that lets her work directly with her hands. Experimenting with combinations of materials and new techniques in printmaking, collage and con- struction serves as a catalyst to push the paintings forward.

The way life becomes art is quite a straightforward process for Speed. Her obsession with the Suprematist works of Malevich started one day as she was sitting on the floor of an antique dealer’s barn. He handed her the first of a number of books which, though badly damaged by fire, still contained a number of beautiful lithographs of various crows and other black birds. When Speed saw the birds’ heads, for some reason she instantly imagined them as attached to heavy black bodies filled with geometric shapes, so she went home and started studying Malevich in depth. She began the series by first cutting the crows’ heads out of the recently acquired books. She then mounted the images on to a support board and commenced constructing the rest of the composition. This process of cutting, gluing, and painting led to series of nine works, entitled The Murder of Kasimir Malevich. The word “murder” in the title does not refer to the corporal act, but to the crows—a “murder” of crows is like a “gaggle” of geese or a “pride” of lions.

A year later she began another homage to Malevich, the Black Square series, inspired by a walk on the railroad tracks in Marfa, Texas. “There were shapes I liked in the track junk," she says. She gathered them up and brought them back to the house where she was staying, arranged them into a series of small sculptures, drew them and then disassembled them again. When she got the pieces back to her Austin studio, she “looked again and then realized they needed black squares to anchor the shapes and limit the possibilities.” She then had twelve identical sheets of paper printed with aquatint squares, once again laid everything out on the floor and started anew, this time including additional elements of found paper, painted wood, and other materials. After weeks of arranging and rearranging these generally incompatible materials, she ended up with the Black Square series, which altogether includes fourteen images.

Spiral Square 2004 aquatint , paper and steel, 22 x 15 inches

The placement of her figures within the picture plane reveals a connection to modern painting, that predates her recent involvement with Malevich—the inventor of non-objective art. This is also obvious in the way she works. The critic, Meyer Shapiro, noted the priority of the image-frame relationship as a characteristic theme shared by both modern art and medieval painting. In addition, her debt to flatness, whether it be from the Italian primitives of the early Renaissance or folk artists, coincides with the flatness of modern art. Despite her rejection of abstraction, the work has a unique Janus-faced relationship to the past and the present. Indeed, her debt seems to belong to neither source, but rather to a special kind of mental space that her quirkiness creates.

The combination of innocence and sophistication in Speed’s work has a compelling allure; her imagery is intense and vivid. The amount of detail she laboriously applies keeps the eye and the mind at work long after other art would become tedious. Speed has an extraor- dinary capacity to absorb and store experience as a per- manent eidetic archive she may access at any time.

Speed has often been identified as a Surrealist.

She rejects such a stylistic categorization, instead identi- fying her work as "pararealism", meaning it is an alter- native to what we normally see. This seems to make sense in terms of its relationship to parapsychology, which is the field of mental telepathy and the percep- tion of the paranormal. It was André Gide who defined artists as "the antenna of the race," referring to their ability to receive and transmit realities that are invisible to others. Certainly, Julie Speed is one such active antenna, constantly picking up signals.

There is a hallucinatory concreteness to her visions that brings to mind intense descriptions of saints in states of rapture and communication with a world beyond our own. It is therefore not surprising that Speed reads and writes poetry. The way she compress- es and laminates images relates not to Stéphane Mallarmé's Symbolist correspondences but to the poet- ry of Amy Lowell and the New England Imagists. The poets’ images do not depend on free association or cryptic references, but rather on the construction of a concrete and specific image that resembles an epiphany or vision.

The deliberate ambiguity of Speed's images resem- bles that of poetry, neither of which can be flattened into a single interpretation. Indeed, the critic William Empson identified seven types of poetic ambiguity. The painter must have at least ten. Her technique appears close to that of the early Netherlandish painters and she has referred to her admiration for Jan van Eyck, yet the meticulous detail in her work is not actually the same, nor is it used for the same purposes.

Her images, although not contrived to elicit emo- tion, do resonate. In response to her 1999 traveling exhibition, Queen of My Room, she received boxes of letters interpreting her paintings. Almost all the expla- nations were completely at odds with anything that had ever crossed her mind. She received a twelve page paper from a mathematician who explained why her paintings were related to his three dimensional mathe- matical theory. Other letters from physicists found that her work also corresponded with their theories. She found these responses mystifying, since she knows vir- tually nothing about math or physics. Several psycho- analysts were convinced that the paintings were a per- sonal cry for help. Evangelical Christians were sure her soul was on fire. There was even a letter that led to a visit from the bomb squad. She delights in the fact that while no two interpretations were the same, each view- er was certain that they had received the correct message.

She also rejects obvious symbolism, although she is aware that some images appear particularly loaded. Still Life with Suicide Bomber # 4 depicts an ear and sunflowers, but the connection to Vincent Van Gogh did not occur to her until someone pointed it out.

Still Life with Suicide Bomber # 4 2003 oil on linen on panel, 24 x 18 inches

Many viewers have questioned Speed about why she sometimes furnishes her figures with a distracting third eye. She rejects the idea that the motif refers to spiritual insight, like the third eye of the Greek prophet Tiresias or Buddhism’s inner eye. For her, it is another element to jolt the viewer, a practical way to show the subject's ambivalence. She constructs the lines that indicate the subject’s dual field of vision, which forms an invisible triangle. Whatever the inspiration, this third eye, which is not in the middle of the forehead or the chest, but just above one of the normal eyes, adds a note of mystery that causes a sense of disorientation. It is as if the pictured figure is actually turning his or her head before us, making it virtually impossible for the viewer to focus.

Part of the pleasure in looking at Speed's paintings is that they evoke both tactile and optical responses that are totally unfamiliar. The costumes decorated with obsessive horror vacui patterns appear prickly when investigated as in Woman with Dogs. These are not precisely trompe l ́oeil but it is a related effect.

The artist is quick to point out that she rejects images that seem too close to her personal experience; instead, she seeks to evoke responses in others, rather than to express anything about herself. Her expression is her incredible talent. Speed does not want to either express herself or to mirror popular culture. She states, “it seems to me that popular culture mirrors itself too much already – one long depressing hall of mirrors".

The paintings are not always conceived in series, but sometimes specific images keep recurring, as if demanding to be painted again. For example, The Dogmatists, III (p. 43) has a predecessor in an earlier version, titled The Dogmatists. She intentionally painted the bodies of the two men locked in mortal combat in a shade of pink that is reminiscent of hairless piglets, which makes their pointless mayhem look all the more ridiculous. The image of the two grimacing knife- wielding men is also related to the gouaches, Dawn of Man/Crack of Dawn and The Rites of Spring , and she intends to make other versions as well.

The Dogmatists III 2007-08 oil on panel, 24 x 24inches

Speed has no logical explanation for why one thing or another engages her attention. Recently, she has become interested in the representation of water, as a result of looking at The Adventures of Hamza, Persian miniatures commissioned by a teenage Mughal emperor around 1550, that were the subject of a show at the Smithsonian. She is fascinated by the stylized rendering of water, which she includes in such gouaches as The Bather (p. 22), The Yellow Boat (p. 18), and Small Pond (p. 41).

She claims to know nothing about color theory except what she has independently deduced. She gets "crushes" on certain colors. For a while she favored umber, a favorite Renaissance pigment, which was com- monly used to paint shadow. Then she turned to Ultramarine Blue, another Renaissance favorite, but the color she returns to most often is Cadmium Red Deep, the color used in many of her figures’ costumes. The skin tone of the face in Untitled, Red (p. 73) is com- prised of red, green and blue mixed together, which produces an effect that lends the subject a choleric look. The smoke pictured in the scene is also red and the figure’s skin reflects the red of the sky. In the gouaches, she crosshatches an entire palette, each color added on in a different layer. In less dramatic

moments, Speed is also inspired by the colors of bugs, birds and plants—which she collects.

Speed admits she would like to have painted freely like Francis Bacon or Edouard Manet, but compulsion requires her to paint close up, possessively reworking surfaces until they become smooth with invisible brush- strokes. She recalls an afternoon spent with the painter John Alexander. Watching Alexander slather paint on the canvas with big muscular gestures inspired Speed to stretch a huge canvas and paint on it with big bold strokes. However, she needed a more intimate relation- ship to her work and was soon standing close to the surface and covering it with her characteristic precise strokes.

Speed’s painstaking technique becomes hallucina- tory, even hallucinogenic, i.e. realer than real—in the sense of an apparition, a visitation for those who expe- rience them. The elaborate patterning in her subject’s clothing contrasts with the sharp dramatic silhouette of forms against the background. She makes no distinc- tion between the sources of her imagery. The daily TV news, an Old Master painting, something she sees that catches her eye in a garden or a museum are all of equal importance as food for her mind and fodder for her art.

The presence of animals, especially monkeys and snakes, recalls the allegorical tradition seen in Renaissance painting. But once again, she drops clues and then sends us off on another track. For example, in Goya’s Monkey (p. 61), a woman faces out, oblivious to the two men battling with cudgels outside the window. The cudgel battle is an element borrowed from one of Goya’s Black Paintings. It is typical of Speed's composi- tions that while horrific activities are taking place, the subjects seem totally distracted and unresponsive to the carnage. It is hard not to see this type of theme as a commentary on the way we have inured ourselves to contemporary catastrophe.

Julie Speed is an iconoclast in the truest sense of the word. Hers is the iconoclasm of a most sophisticat- ed outsider artist. Incongruity is always present in Speed's work. She gives a nod to standard iconogra- phy but deviates from it by filling in with disparate images that more closely resemble The Yellow Submarine than Jan van Eyck. Everything reminds you of something else in this absurdist information-over- loaded short circuit. The Germans have a word for the uncanny, unheimlich, which they use to describe the nightmarish imagery of the Romantic painters such as Johann Heinrich Fuseli. Fuseli, like Bosch, was considered a Surrealist ancestor.

Speed is, however, neither moralist nor Surrealist. Her imagery has more in common with the absurdist lit- erature and theater of Eugène Ionesco. Although Speed is hardly a traditionalist, her work often seems to belong to the tradition of the images of folly and of the topsy-turvy world that was dominant in the work of Kleinmeister of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, when the world was certainly a mess and none of the reigning orders and structures seemed to make sense any longer. This was, of course, the great period of "monkey business” when the images of monkeys, the unclean apes of man, cavorted shamelessly through a world turned upside down. This tradition of the topsy- turvy upside-down world is familiar in the works of Dutch artists like Adrian van Ostade, as well as in the many works of the turbulent times in the sixteenth cen- tury when the Iconoclasts, considered heretics, chal- lenged official orthodoxy. These images of folly also inspired Goya's Caprichos, which Speed has pointed to as one of her sources.

Speed is able to open the Pandora's Box of the individual, as well as the Collective Unconscious. Her imagery is simply what she has taken in, as it comes out, mixed and unpurified. It is then recontextualized and mixed with other images to concoct a kind of cre- ative bouillabaisse. Hers is a Gothic imagination informed by contemporary experience. Her excess of detail transfixes the eye. In the end, it is a challenging, mystifying and altogether enjoyable experience.

BARBARA ROSE, NY 2005

Tracking

by Julie Speed (Courtesy of the University of Texas Press)

Sometimes pictures come singly, sometimes from a germ, sometimes from scratch, but always one thing leads to the next in a way that feels inevitable.

Most people assume that an artist begins with a coherent thought or idea and then, if it’s a figurative work, basically just illustrates that idea, and if she’s really, really deep, then the illustration might not actually be a picture of what it’s a picture of but instead symbolize some specific other thing and, if the viewer has the secret decoder ring or museum wall text, they will be able to figure out the “correct” interpretation.

A stranger wandered in off the street a couple of days ago, spent some time looking at a large drawing that I was working on of a bunch of old naked guys fighting each other with pink sticks, and asked, “What do they represent?” How do I answer that? Do I say, oh, they represent the fighting in Iraq or Thermopylae or the cock-up last night down at Joe’s? What’s the point? They’re not real, so my thoughts, even my really, really deep thoughts, about them carry no more weight than anyone else’s.

In addition, the elements which people usually interpret as narrative are more often the product of the composition than vice versa. If there is a spot of red in a certain place it is more likely there because I wanted red than because I wanted blood. Composition comes first. The second most interesting part happens as the abstract skeleton gradually takes on its figurative flesh.

Fight Club II 2007 graphite & gouache, 40 x 58.50 inches

In 2002 I bought the ruins of a set of beautiful smoke-damaged nineteenth-century leather- bound books: Reports of Explorations and Surveys, which had been salvaged from the last library fire of the legendary Texas antiquarian book dealer, John Jenkins, shortly before his violent murder/suicide (still debated) in 1989. Inside the books were hundreds of odd and beautiful, off- kilter and moldy lithographs of birds and fish, snakes and plants, rats, moles, and, best of all . . . black bird heads. No bodies, just heads, which leapt off the pages and attached themselves, instantly and quite sharply in my mind’s eye, to curvilinear black bodies stuffed with geometric shapes on a white background. The images were so overwhelming that I became deaf for a min- ute or two. The man who was selling the books spoke as, one after another, he handed over the sooty volumes. His lips moved, but I literally couldn’t hear.

The geometric shapes led me to study Russian constructivism and, from there, to make the paintings which collectively became The Murder of Kasimir Malevich. The title came from the black birds, a “murder of crows” being the same as a “pride of lions” or a “wake of buzzards.”

Starting with a pile of cut boards, a parallel ruler, and a handful of ancient plastic triangles found in the back of a drawer, I drew shapes endlessly until I dreamed geometry at night. During the day the background noise was continuous news of the anthrax attacks which had followed hard on the heels of 9/ll. Fear and speculation were rampant as to all the possible ways in which various nightmarish biological agents could be weaponized and distributed. In Texas death seemed most likely to be delivered by crop duster.

Strangely these fears dovetailed with my reading at the time about Malevich’s theory of the “additional element” (or “supplemental element”), which he came up with while he was director of the State Institute of Artistic Culture in Leningrad and teaching in what he called the “Department of Bacteriology of Art.” According to his theory, there are specific shapes in art (which he and his students isolated and diagrammed) which he believed could, like a tuberculosis bacillus, literally “infect” an artist who uses them. At different times both he and his second wife contracted the “white death.” She died of it.

The Murder of Kasimir Malevich # 8 (Cropduster) 2003 acrylic & collage on panel, 36 x 30 inches

The ways in which events collide with composition to make a painting is a funny thing. During most of the time I was working on The Murder of Kasimir Malevich #8 (later nicknamed “Cropduster”), the two yellow triangles and the black bird head were its reasons for being. All the big shapes had been worked out and the painting was almost finished when it became apparent that it needed narrow black shapes and small open white shapes to complete the balance. Because I’d been looking at charts of Malevich’s “additional elements,” I stole one of the sickle shapes from his diagrams of infectious art to supply the narrow black shape and then repeated it, making wings. For the open shapes letters seemed right, so, since I had just finished reading a long terrifying article about the stunningly adaptive properties of the smallpox virus, the letters V A R I O L A suggested themselves to me. The very last thing was to almost accidentally paint a chute on the bird, and only then came the realization that it was a lethal crop duster. It sounds ridiculous even to me that it should be such an ass-backwards process, but it almost always is.

In the large 2007 graphite and gouache drawings of the pink-bottomed guys hitting each other (Fight Club, Fight Club II, and The Revisionist), the angles of the arm and leg bones of all the fighting men, and thus their positions in relation to each other and to the rectangle of the paper, are all governed by the tangle of triangles underneath. The flesh came later.

In all the pink cake paintings so far (One Pink Cake, Flounder, Three Pink Cakes, Happy Fuck- ing Birthday, and Watch for Falling Rocks), the cakes are there primarily because they are about the same size as human heads. Those paintings began with abstract geometric drawings of triangles formed by an overall design composed of circles and ovals (cakes and heads) intersected by straight lines.

On the flip representational side, the trees and sticks of Revelations, Bivouac, and Crusades are pink because one morning at dawn last winter, I opened my eyes to find that the sun’s rays coming up over the church roof next door had turned the bark of the leafless pecan trees in the backyard bright pink. That pink then strayed from the trees, to the sticks, to the cakes, to the butt-cheeks of the fighting guys.

While all the “art” concerns—new media/old media/, conceptual/aesthetic, abstract/repre- sentational, etc.—are great fun to talk about, they seem sort of beside the point when you actually get down to work.

In the last few years I’ve begun to notice a little “click” that I can “hear” as each shape (or color, volume, line, etc.) falls into place. Because of its precise nature (it’s either right or not right—there’s no “close”) my guess is that there’s a mathematical basis to it. I think someone, though not me, could write an equation defining it.

There are also shapes inside of shapes, patterns inside of patterns, and when the main composition of a painting is more or less settled, I happily pull up a chair, put on magnifying spectacles, pick up smaller brushes, and re-enter the painting, this time treating each square inch or so as if it were a tiny abstract canvas.

Just as the daily practice of drawing gradually builds up the communication between hand and eye, in the same physical way, pitting a small piece of paper text against a hunk of wood or iron in collage is something you can practice and get better at. Arranging different-sized spheres on various-sized open planes, then various-sized closed planes and so on, over and over, is almost endlessly absorbing. The mathematical relationship between the spheres, whatever it is, is like something I already know but can’t quite remember, or something not actually lost so much as serially misplaced. Whatever it is, it’s also there in everyday things like cooking, gardening, or idly arranging sticks and rocks in the grass. No matter what you’re constructing—a painting, a song, a story, a stone wall, minestrone, whatever—there is a pure satisfaction to be felt in “hearing” those little click echoes when you get it right.

It took several weeks and thousands of combinations to arrange the balls of snakes in Axis, Falling Snakes, and Trick Snakes. I would twine them one way and they would be wrong, then the next and the next and the next . . . wrong, wrong, wrong. Then, suddenly “click,” they would be right, and I had to get them glued down quickly before they slipped out of whack again. By “learning” the snakes I was also, for the future, learning the tangle of human limbs in the various fighting men, the curves of the tree limbs in Revelations, the eddies of the water in Adrift, and so on.

Trick Snakes 2007 collage, gouache, acrylic and wood on paper, 30 x 22 inches

The abstract aspects of my work I think of like the bassline or rhythm section, and laid on top of that is the daily input of current events, books I’ve read, whatever thoughts are occupying me at the time. That’s the melody, or figuration. If the two weave in and out of each other in just the right way then the work is good. If either aspect is out of balance then the work is unsuccessful.

Take, for instance, the painting Frogpond, which began with two irregular charcoal blobs on a large canvas. The blobs might have been inspired by an illustration of cells dividing, or maybe the shapes of rocks in a river or a pattern of steam drippings on the bathroom wall. I don’t remember. When I drew a horizon line at the top of the canvas the blobs turned into figures standing chest-deep in an ocean, so I added battleships on the horizon (my father was building a model of the battleship Potemkin at the time). But the straight line bothered me so I curved it, erased the battleships, and the curved line changed the ocean first into a planet and then into a pond. By then, I’d been working for a couple of years on learning a new (for me) way of depicting water, having been inspired by a book called The Adventures of Hamza, a series of beautifully intricate adventure paintings commissioned by the teenage Mughal emperor Abkar when he came to power in the middle of the sixteenth century.

Because it was a pond and the men were by that time pink, I added frogs with their pink and white bellies to make smaller spots of the same intensity and color and then water lilies for the same reason, all in triangles. Maybe the frogs were just there because I wanted pink and white blobs in a certain arrangement, but also I was thinking of frogs, because I had just been reading about the alarming worldwide drop in the frog population caused by our spilled chemical waste seeping into their vulnerable permeable skin. For whatever reason, the crucified frog at the top of the painting was one of the last elements when, too late, I realized that the top center pink and white spot needed to be higher, but by then the painting was a month and a half old so there was no going back. The only visual solution I could think of was to raise him up. He looked stupid just jumping so I put him on a cross, which of course added a whole new basket of questions on top of the first layer. Are the men polluting the pond? What is their relationship to each other? Are they farting? Is that why the frogs are all dead? Are they dead or have they just fainted from the fumes? Or are they faking? Has the crucified frog died for the sins of the chubby pink men (they look uncomfortable and perhaps a little guilty), or has he died for the sins of the other frogs? Can frogs sin? Of course none of my ruminations on pollution or frog sin have any more validity than whatever the viewer brings to the painting. That’s why it’s art, and not homework.

Frogpond, 2005-06, oil on linen, 30 x 40 inches

The New York Times

Art in Review; Julie Speed

By GRACE GLUECK

Published: January 27, 2006

Gerald Peters Gallery

24 East 78th Street, Manhattan

Through Feb. 25

Julie Speed is a quirky neo-Surrealist whose inspirations range from old master and Mughal painting to that 20th-century master of arcana, John Graham. In her show here, ''Bible Studies,'' she paints robust, red-faced peasant-type people with odd ways.

One, wearing nothing but a red bathing cap and an angry expression, stands up to her thighs in a stylized body of water as she reels in a red fish. In ''Evil Twin,'' a double portrait of two bun-coiffed women, one sticks out her tongue as she gazes toward the viewer. Religious symbolism abounds in this work, as in ''Little Fishes,'' which depicts a grim-faced bishop standing over an open book on a table, as a three-armed infant, naked in a nearby high chair, tries to catch tiny fishes flying through an open window.

But Ms. Speed's chef d'oeuvre is ''Ad Referendum,'' a suite of complex etchings, each with a different ground, that appear to be of a homey prelate resembling Pope John Paul II. His garment and biretta are adorned with collaged fragments of images of atrocities and book-burning from several sources, including illustrations by Gustave Dore and old Bibles.

Lovable this imagery isn't, but it grows on you, largely because Ms. Speed's grasp of it is firm and her technical mastery impressive.